Sturdier tips. My earlier Greenland paddles have held up OK, with normal dents and dings. Yet, the tips have taken a beating. Evan suggested hardwood tips for this one. That’s what that darker lumber pictured in part 1 is for. It is one of the Mora family, several times heavier than cedar, hard and dense. My goal is to use a little bit at each tip, just enough for protection, not enough to be too heavy.

My foremost concern is how to keep the tips attached. Thin pieces don’t leave much opportunity for advanced joinery (T&G, biscuits, etc.) and end-grain to end-grain gluing is always a weak option. Let’s improve the amount of surface area for glue by using a substantial dovetail.

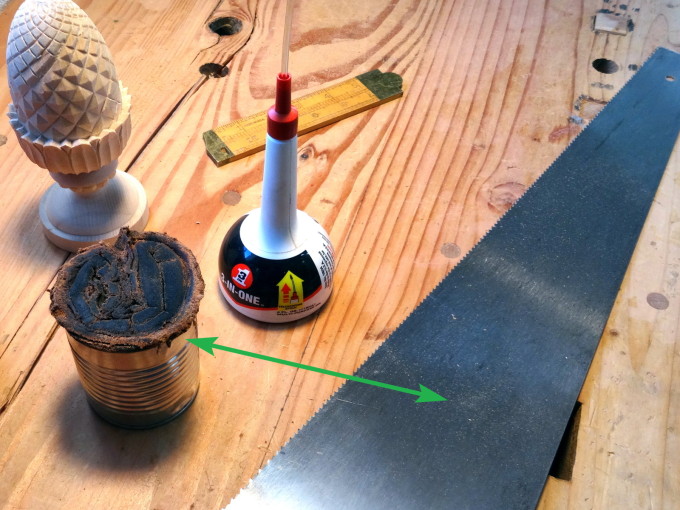

First, the plank thickness has to be reduced. Time for resawing. Start with the kerfing plane, finish with a rip saw. Then, layout the parts and cut the dovetails. Zowie, that wood is hard!

As always, that bow saw, which weighs only 12.3 ounces easily cut the outer shape. For final smoothing, I used a sanding disc on the treadle lathe.

Next: attach the tips with high grade epoxy. And while the epoxy sets, clean the shop. Two partial paddles sit on the horses (one is a shorter “storm paddle”) while all the stuff that’s not paddle litters the floor. My habit is to let epoxy cure 20-24 hours no matter what it says on the container. Then, test by rough shaping with sharp tools. Knowing the tips won’t break off, I’ll get to the finish shaping the rest of the paddle shortly.