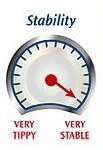

One of the factors for selecting the Mill Creek 13 for the Eva Too build was stability. The CLC Boats site had this confidence inspiring meter showing the boat to be very stable. That really appealed to Eva.

One of the factors for selecting the Mill Creek 13 for the Eva Too build was stability. The CLC Boats site had this confidence inspiring meter showing the boat to be very stable. That really appealed to Eva.

We’ve had both boats out several times recently and have gotten used to their rolling nature. Yesterday, I had no water sensitive electronics aboard, so I tested “secondary stability.” That’s the kind of stability that a hull exhibits (or doesn’t) when rolled off of its normal keel. My tests were simple and didn’t go all the way to a complete capsize. I simply leaned over until it felt as though I was about to fall out of the boat. Each boat behaved very nicely. They rolled over onto one of their planks and remained stable. I was able to roll to the point of having a rub rail submerged.

In the end, we need another notch on that meter. It was harder to get the Fiddlehead over to rub rail submersion than it was the Mill Creek. I think one would literally fall out of the boat before either one rolls enough to capsize.